Headline News

Remembering everyday violence against women and girls on Dec. 6

It’s the National Day of Remembrance for the 14 women who were killed at the L’école Polytechnique in Montréal for being women and for being students in a discipline that, at the time, was wholly male-defined.

Across the nation and on different social media platforms, the remembrance is being marked by symbols and personal testimonies.

It’s a reminder that the violence has not ended despite the overworked sector of civil society — women on the front lines in shelters, rape crisis centres and counselling centres.

While the collective outpouring of grief that marks this day is anchored in a remembrance of the murders of women at the polytechnique, it is also imperative that high-profile acts of violence don’t overshadow the everyday, routine forms of violence that women suffer.

Six deaths every hour

The report of the Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and Accountability notes that around the world, every hour, six women are killed by men they know.

Femicide, or the killing of women because they are women, is underpinned by patriarchal ideologies that define how women should comport themselves. This ideology, grounded in the belief that men own women and that women need to be controlled, is also at the heart of gender inequities.

Although the tragic events at the polytechnique occurred 30 years ago, women and girls in Canada today continue to suffer from the effects of patriarchal ideologies. They experience that patriarchy differently, depending on where they are located in the matrix of domination — the axes of race, class, gender, religion, age, ableism and sexuality that criss-cross society and heighten the vulnerabilities of some women more than others.

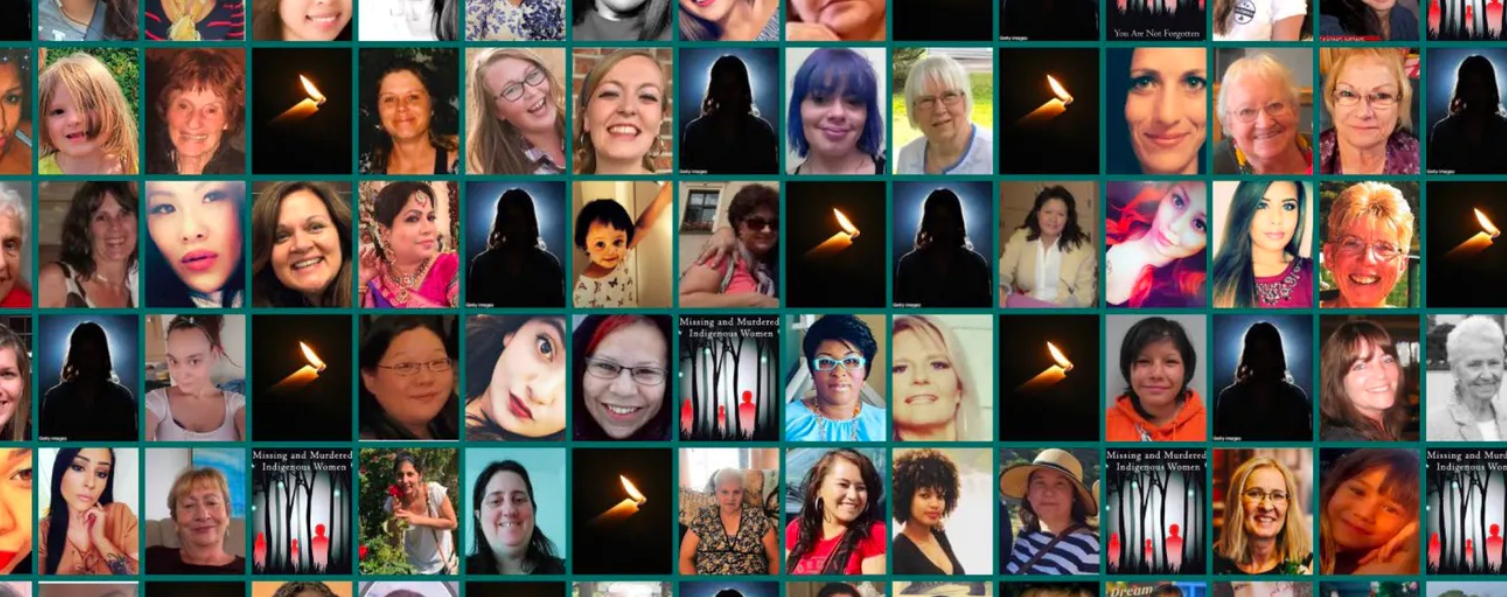

The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls Inquiry reveals the extent to which Indigenous women, girls and LGBTQ+ are dehumanized and subjected to violence. Canadian statistics reveal that a woman is killed every five days by an intimate partner or a family member. Murder is the finality in the continuum of violence that women and girls experience.

Privilege does not shield

We can’t forget these deaths — the murders that are reported in short, terse paragraphs in the news, or that are accounted for only by organizations situated in particular communities, or remembered by close family and kin.

These deaths testify to the presence and power of patriarchal values and traditions. Similarly, while groups like the incels have attracted power and attention, they remain the tip of the iceberg. There are countless everyday expressions of male power and violence that work to constrain women.

Much like how the focus on racism that tends to be restricted to the actions of extreme hate groups and their acts of violence, the systemic, everyday racism that permeates society also needs to be named and dealt with.

The takeaway of the murders at the polytechnique is this — violence that is endemic and coursing through society is violence that crosses the boundaries of race, class, age, sexuality, gender and religion. It’s violence that is anchored in the view that women are inferior, less than men, and to be controlled by men.

The 14 women killed at the polytechnique were white, middle class and educated, and this did not shield them from patriarchal violence. What then about the women who have no such privileges? How best can we remember them?

Headline News

How Canadian churches are helping their communities cope with the wildfires

As wildfires burn across Canada, churches are finding ways to support their members and the broader community directly impacted by the crisis.

According to the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre, as of June 13, there are 462 active fires across Canada – and 236 of them classified as out of control fires.

Whether it’s through phone calls or donations to community members, here’s how a few churches across Canada are handling active wildfires and the aftermath in their regions.

Westwood Hills, N.S.: St. Nicholas Anglican Church

In Nova Scotia, St. Nicholas Anglican Church and other churches in the area are collecting money for grocery cards to give to families impacted by the Tantallon wildfire.

Right outside of Halifax, N.S., the Tantallon wildfire destroyed 151 homes. More than 16,000 people evacuated the area due to the fire.

The fire is now considered contained, but Tanya Moxley, the treasurer at St. Nicholas is organizing efforts to get grocery gift cards into the hands of impacted families.

As of June 12, four churches in the area – St. Nicholas, Parish of French Village, St Margaret of Scotland and St John the Evangelist – raised nearly $3,500. The money will be split for families’ groceries between five schools in the area impacted by the wildfire.

Moxley said she felt driven to raise this money after she heard the principal of her child’s school was using his own money to buy groceries for impacted families in their area.

“[For] most of those people who were evacuated, the power was off in their subdivision for three, four or five days,” she said. “Even though they went home and their house was still standing, the power was off and they lost all their groceries.”

Moxley said many people in the area are still “reeling” from the fires. She said the church has an important role to help community members during this time.

“We’re called to feed the hungry and clothe the naked and house the homeless and all that stuff, right? So this is it. This is like where the rubber hits the road.”

Headline News

Is it ever OK to steal from a grocery store?

Mythologized in the legend of Robin Hood and lyricized in Les Misérables, it’s a debate as old as time: is it ever permissible to steal food? And if so, under what conditions? Now, amid Canada’s affordability crisis, the dilemma has extended beyond theatrical debate and into grocery stores.

Although the idea that theft is wrong is both a legally enshrined and socially accepted norm, the price of groceries can also feel criminally high to some — industry data shows that grocery stores can lose between $2,000 and $5,000 a week on average from theft. According to Statistics Canada, most grocery item price increases surged by double digits between 2021 and 2022. To no one’s surprise, grocery store theft is reportedly on the rise as a result. And if recent coverage of the issue rings true, some Canadians don’t feel bad about shoplifting. But should they?

Kieran Oberman, an associate professor of philosophy at the London School of Economics and Political Science in the United Kingdom, coined the term “re-distributive theft” in his 2012 paper “Is Theft Wrong?” In simplest terms, redistributive theft is based on the idea that people with too little could ethically take from those who have too much.

“Everybody, when they think about it, accepts that theft is sometimes permissible if you make the case extreme enough,” Oberman tells me over Zoom. “The question is, when exactly is it permissible?”

Almost no one, Oberman argues, believes the current distribution of wealth across the world is just. We have an inkling that theft is bad, but that inequality is too. As more and more Canadians feel the pinch of inflation, grocery store heirs accumulate riches — Loblaw chair and president Galen Weston, for instance, received a 55 percent boost in compensation in 2022, taking in around $8.4 million for the year. Should someone struggling with rising prices feel guilty when they, say, “forget” to scan a bundle of zucchini?

Headline News

The homeless refugee crisis in Toronto illustrates Canada’s broken promises

UPDATE 07/18/2023: A coalition of groups arranged a bus to relocate refugees to temporarily stay at a North York church on Monday evening, according to CBC, CP24 and Toronto Star reports.

Canadians live in a time of threadbare morality. Nowhere is this more obvious than in Toronto’s entertainment district, where partygoers delight in spending disposable income while skirting refugees sleeping on sidewalks. The growing pile of luggage at the downtown corner of Peter and Richmond streets resembles the lost baggage section at Pearson airport but is the broken-hearted terminus at the centre of a cruel city.

At the crux of a refugee funding war between the municipal and federal governments are those who have fled persecution for the promise of Canada’s protection. Until June 1, asylum seekers used to arrive at the airport and be sent to Toronto’s Streets to Homes Referral Assessment Centre at 129 Peter St. in search of shelter beds. Now, Toronto’s overcrowded shelter system is closed to these newcomers, so they sleep on the street.

New mayor Olivia Chow pushed the federal government Wednesday for at least $160 million to cope with the surge of refugees in the shelter system. She rightly highlights that refugees are a federal responsibility. In response, the department of Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada points to hundreds of millions in dollars already allocated to cities across Canada through the Interim Housing Assistance Program, while Ontario says it has given nearly $100 million to organizations that support refugees. But these efforts are simply not enough to deliver on Canada’s benevolent promise to the world’s most vulnerable.

The lack of federal generosity and finger-pointing by the city has orchestrated a moral crisis. It’s reminiscent of the crisis south of the border, where Texas governor Greg Abbott keeps bussing migrants to cities located in northern Democratic states. Without the necessary resources, information, and sometimes the language skills needed to navigate the bureaucratic mazes, those who fled turbulent homelands for Canada have become political pawns.

But Torontonians haven’t always been this callous.

In Ireland Park, at Lake Ontario’s edge, five statues of gaunt and grateful refugees gaze at their new home: Toronto circa 1847. These statues honour a time when Toronto, with a population of only 20,000 people, welcomed 38,500 famine-stricken migrants from Ireland. It paralleled the “Come From Away” event of 9/11 in Gander, N.L., where the population doubled overnight, and the people discovered there was indeed more than enough for all. It was a time when the city lived up to its moniker as “Toronto, The Good.”

Now, as a wealthy city of three million people, the city’s residents are tasked with supporting far fewer newcomers. Can we not recognize the absurdity in claiming scarcity?