Headline News

The Anxious Triumph by Donald Sassoon – why capitalism leads to crisis

On 20 January 1981, in his inaugural address as 40th president of the United States, Ronald Reagan declared: “Government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem.” It was the soundbite that defined the end of the 20th century. “Rolling back the state” became the mission of the “market revolution” spearheaded by Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

In fact, as Donald Sassoon argues in The Anxious Triumph, the idea that the state and the capitalist economy can thrive apart is nonsense. The modern state and economy are twins born together in the 17th century. Through the age of absolutism and the great 18th-century revolutions, their relationship matured into one of ever-greater interdependence. This was most evident in the newcomer nations of the 19th century, like Meiji Japan or Bismarckian Germany. But it was every bit as true of a “liberal” power like Victorian Britain.

How precisely economic and political interests are articulated varies across the world and depends very much on a nation’s place in the international order. Part of the reason classical liberalism could acquire such a hold on Victorian Britain was that the UK moved first. Having constructed a powerful combination of a centralised fiscal state and a global empire, the UK didn’t flesh out its nation state apparatus or articulate a strong vision of a national economy until the 20th century. But then, as the historian David Edgerton has recently shown, it did so with a vengeance.

When you say that you want to roll back the state, what you really mean is that you want to reconfigure the relationship. Libertarians, down to today’s advocates of cryptocurrency, may dream. But the divorce they fantasise about is not a utopia but a nightmare. Insofar as it has ever existed, anarcho-capitalism is a product of disastrous state failure. Its life is nasty, brutish and short.

Government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem Ronald Reagan

If the problem of the relationship of government and the economy is nevertheless posed over and over again, it is because on both sides it is fraught with tension. In order to function, as Sassoon stresses, states need politics, and that involves squabbling elites and more or less mobilised masses. Mass politics and modern ideologies, above all nationalism, have explosive potential. Indeed, if taken seriously, the very notion of politics as a process of collective choice and self-empowerment is antithetical to an economic system based on binding contracts between entrenched private interests that have no regard for the political collectivity.

A long line of liberals down to the neoliberals of our own age draw the conclusion that the solution is to tame politics: through law, international treaties, independent central banks and so on. That, not surprisingly, draws political opposition, both from the left and the right. But even more destabilising is the fact that liberals are on the whole hopelessly unrealistic about what actually makes the economy tick.

The arcadia of self-equilibrating markets, falsely attributed to Adam Smith, was one such fantasy. As Sassoon shows, even in the 19th century, not many people really believed in it. The 20th-century version was the macroeconomic idea of the national economy that could be governed like a machine. That, as we now realise, was in large part an artefact of national economic statistics. Numbers like GDP gave us a false sense of common interest in enlarging the collective pie.

Neither the utopian notion of the “invisible hand” nor the Lego-brick conception of the national economy captures the dynamic, disruptive, creative destruction that is the reality of actually existing capitalism. It is a protean force perpetually generating inequality, crises and the all-pervasive anxiety that gives Sassoon’s book its title.

There have been periods in which the tensions in this fraught relationship have been highly contained. The mid-20th century, the moment of the Beveridgean welfare state, was one when the state and economy were held in a fine balance. The periods before 1945 and from the 1970s onwards have been more unstable.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest Margaret Thatcher with Reagan in 1981. Photograph: Bettmann/Bettmann Archive

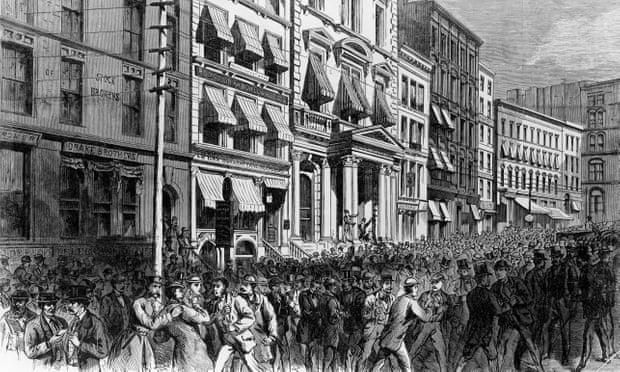

Sassoon’s book speaks to the present by conjuring up the era between the 1850s and 1914, in which the tensions between global capitalism and modern politics came clearly to the fore. This was the first age of modern politics, if not of democracy – the age of Gladstone, Disraeli, Lincoln and Bismarck. It was the age of imperialism and early experiments in social insurance. It was the age of railways, steamships and the boom and bust of the global cotton industry.

Sassoon offers us a sprawling map, studded with fascinating details. Curious about the urban poor in 19th-century Naples? Want to know why liberalism was stunted in late-19th-century Romania? Sassoon is your man. Ever heard of the city of Elkader, Iowa, founded in 1846? No, neither had I. It was named, it turns out, in honour of the Emir Abd el-Kader, leader of the resistance against the French occupation of Algeria.

As one is thrown from cameo to improbable cameo, reading Sassoon becomes a hallucinatory experience. Insights are proffered and then repeated, sometimes several times. Familiar facts mingle with jaw-dropping novelties. The chronology drifts, at times roaring into the present before retracting not just to the 19th century, but deep into the 18th.

Is there some artful design at work behind the apparent confusion? Is the book’s swirling disorder meant to mirror its subject? If, as Sassoon remarks, capitalism moves “without a goal or a project”, would it be misleading for a historian to impose too much order or narrative coherence? If so, it is a pitfall Sassoon triumphantly avoids. But in a book of 758 pages, the effect is mind-boggling, and not in a good way.

Those craving order may do better to approach Sassoon’s book chapter by chapter. Skip over the preface in which he impatiently refuses to define capitalism and the first chapters in which he meanders through the history of 19th-century state formation. Home in, instead, on his detailed discussion of the role of the Japanese elite in industrialisation, or savour his classically Gramscian reading of the failure of the Italian bourgeoisie. Even better is Sassoon’s discussion of the global spread of democratic political practice before 1914. Skip the chapter that narrates the history of colonialism as a rather moth-eaten house of horrors. Others do anti-imperialism more convincingly. Instead, enjoy Sassoon’s opinionated treatment of French and British parliamentary debates about the rationale of empire.

Or, you could start near the end, where one of Sassoon’s best chapters describes how the great recession of 1873 sparked an awareness of globalisation and triggered a wave of protectionism. He surveys the French debate with real flair but is far too dismissive of protectionism in Britain. It was never “fashionable” he blithely tells us, waving Joe Chamberlain aside.

But read on from there and you are in for a final surprise. Suddenly and without warning, just short of 1914 Sassoon calls a halt. From the trade wars of the early 20th century he jumps into the future. Vaulting over the first and second world wars, he takes us on a sweeping overview of pro- and anti-capitalist politics, complete with nods to Venezuela’s die-hard Chavistas, and Hyman Minsky, the prophet of the 2008 crisis. It is quirkily brilliant. But it is also a diversion. A history of gilded-age capitalism that rightly insists on the inextricable entanglement of the economy and state power, but which does not address the first world war, lapses into nostalgia. It is a puzzling end to a puzzling book.

Headline News

How Canadian churches are helping their communities cope with the wildfires

As wildfires burn across Canada, churches are finding ways to support their members and the broader community directly impacted by the crisis.

According to the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre, as of June 13, there are 462 active fires across Canada – and 236 of them classified as out of control fires.

Whether it’s through phone calls or donations to community members, here’s how a few churches across Canada are handling active wildfires and the aftermath in their regions.

Westwood Hills, N.S.: St. Nicholas Anglican Church

In Nova Scotia, St. Nicholas Anglican Church and other churches in the area are collecting money for grocery cards to give to families impacted by the Tantallon wildfire.

Right outside of Halifax, N.S., the Tantallon wildfire destroyed 151 homes. More than 16,000 people evacuated the area due to the fire.

The fire is now considered contained, but Tanya Moxley, the treasurer at St. Nicholas is organizing efforts to get grocery gift cards into the hands of impacted families.

As of June 12, four churches in the area – St. Nicholas, Parish of French Village, St Margaret of Scotland and St John the Evangelist – raised nearly $3,500. The money will be split for families’ groceries between five schools in the area impacted by the wildfire.

Moxley said she felt driven to raise this money after she heard the principal of her child’s school was using his own money to buy groceries for impacted families in their area.

“[For] most of those people who were evacuated, the power was off in their subdivision for three, four or five days,” she said. “Even though they went home and their house was still standing, the power was off and they lost all their groceries.”

Moxley said many people in the area are still “reeling” from the fires. She said the church has an important role to help community members during this time.

“We’re called to feed the hungry and clothe the naked and house the homeless and all that stuff, right? So this is it. This is like where the rubber hits the road.”

Headline News

Is it ever OK to steal from a grocery store?

Mythologized in the legend of Robin Hood and lyricized in Les Misérables, it’s a debate as old as time: is it ever permissible to steal food? And if so, under what conditions? Now, amid Canada’s affordability crisis, the dilemma has extended beyond theatrical debate and into grocery stores.

Although the idea that theft is wrong is both a legally enshrined and socially accepted norm, the price of groceries can also feel criminally high to some — industry data shows that grocery stores can lose between $2,000 and $5,000 a week on average from theft. According to Statistics Canada, most grocery item price increases surged by double digits between 2021 and 2022. To no one’s surprise, grocery store theft is reportedly on the rise as a result. And if recent coverage of the issue rings true, some Canadians don’t feel bad about shoplifting. But should they?

Kieran Oberman, an associate professor of philosophy at the London School of Economics and Political Science in the United Kingdom, coined the term “re-distributive theft” in his 2012 paper “Is Theft Wrong?” In simplest terms, redistributive theft is based on the idea that people with too little could ethically take from those who have too much.

“Everybody, when they think about it, accepts that theft is sometimes permissible if you make the case extreme enough,” Oberman tells me over Zoom. “The question is, when exactly is it permissible?”

Almost no one, Oberman argues, believes the current distribution of wealth across the world is just. We have an inkling that theft is bad, but that inequality is too. As more and more Canadians feel the pinch of inflation, grocery store heirs accumulate riches — Loblaw chair and president Galen Weston, for instance, received a 55 percent boost in compensation in 2022, taking in around $8.4 million for the year. Should someone struggling with rising prices feel guilty when they, say, “forget” to scan a bundle of zucchini?

Headline News

The homeless refugee crisis in Toronto illustrates Canada’s broken promises

UPDATE 07/18/2023: A coalition of groups arranged a bus to relocate refugees to temporarily stay at a North York church on Monday evening, according to CBC, CP24 and Toronto Star reports.

Canadians live in a time of threadbare morality. Nowhere is this more obvious than in Toronto’s entertainment district, where partygoers delight in spending disposable income while skirting refugees sleeping on sidewalks. The growing pile of luggage at the downtown corner of Peter and Richmond streets resembles the lost baggage section at Pearson airport but is the broken-hearted terminus at the centre of a cruel city.

At the crux of a refugee funding war between the municipal and federal governments are those who have fled persecution for the promise of Canada’s protection. Until June 1, asylum seekers used to arrive at the airport and be sent to Toronto’s Streets to Homes Referral Assessment Centre at 129 Peter St. in search of shelter beds. Now, Toronto’s overcrowded shelter system is closed to these newcomers, so they sleep on the street.

New mayor Olivia Chow pushed the federal government Wednesday for at least $160 million to cope with the surge of refugees in the shelter system. She rightly highlights that refugees are a federal responsibility. In response, the department of Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada points to hundreds of millions in dollars already allocated to cities across Canada through the Interim Housing Assistance Program, while Ontario says it has given nearly $100 million to organizations that support refugees. But these efforts are simply not enough to deliver on Canada’s benevolent promise to the world’s most vulnerable.

The lack of federal generosity and finger-pointing by the city has orchestrated a moral crisis. It’s reminiscent of the crisis south of the border, where Texas governor Greg Abbott keeps bussing migrants to cities located in northern Democratic states. Without the necessary resources, information, and sometimes the language skills needed to navigate the bureaucratic mazes, those who fled turbulent homelands for Canada have become political pawns.

But Torontonians haven’t always been this callous.

In Ireland Park, at Lake Ontario’s edge, five statues of gaunt and grateful refugees gaze at their new home: Toronto circa 1847. These statues honour a time when Toronto, with a population of only 20,000 people, welcomed 38,500 famine-stricken migrants from Ireland. It paralleled the “Come From Away” event of 9/11 in Gander, N.L., where the population doubled overnight, and the people discovered there was indeed more than enough for all. It was a time when the city lived up to its moniker as “Toronto, The Good.”

Now, as a wealthy city of three million people, the city’s residents are tasked with supporting far fewer newcomers. Can we not recognize the absurdity in claiming scarcity?