Editorials

LETTER: Who does profits from capitalism benefit?

Words we think we know – democracy, capitalism, socialism, Christianity, justice – are not simple terms. There are many variations and definitions of each. And they evolve.

Take, for example, capitalism. Many think that it simply means profit. Profit made by investment. In market economies, goods and products are generated and sold for profit. But there are several kinds of market economies. For example, liberated (Britain) and coordinated (Germany), which operate differently. Today, we have a service economy. Produced goods are only a fraction of our economy.

Some think that the only responsibility of capitalism is to make a profit and growing it as fast as possible. Profits for whom? A single owner? A mass of stockholders? Mutually shared by owners, managers, staff, salespeople and production workers? The government? The nation? A multinational corporation whose profits may appear largely in any country it chooses?

It is held to be proper that the income from renting one’s labor to an employer should be taxed for the benefit of society as is renting out your property or profits made from producing goods or providing services, or saving money in bank accounts. But at different rates? How about inheriting great wealth from one’s grandparents? Is gaining a profit by using sophisticated computer systems to jiggle stock market prices taxed at every purchase and sale like purchases in a store?

Technological advances generated by government supported military or space research lead to many profits. But for whom?

Editorials

Our Love-Hate Relationship with Gimmicks

When Jennifer Egan’s novel “A Visit from the Goon Squad” won the Pulitzer Prize, in 2011, much fuss was made over its penultimate chapter, which presents the diary of a twelve-year-old girl in the form of a seventy-six-page PowerPoint presentation. Despite the nearly universal acclaim that the novel had received, critics had trouble deciding whether the PowerPoint was a dazzling, avant-garde innovation or, as one reviewer described it, “a wacky literary gimmick,” a cheap trick that diminished the over-all value of the novel. In an interview with Egan, the novelist Heidi Julavits confessed to dreading the chapter before she read it, and then experiencing a happy relief once she had. “I live in fear of the gimmicky story that fails to rise above its gimmick,” she said. “But within a few pages I totally forgot about the PowerPoint presentation, that’s how ungimmicky your gimmick was.”

The word “gimmick” is believed to come from “gimac,” an anagram of “magic.” The word was likely first used by magicians, gamblers, and swindlers in the nineteen-twenties to refer to the props they wielded to attract, and to misdirect, attention—and sometimes, according to “The Wise-Crack Dictionary,” from 1926, to turn “a fair game crooked.” From such duplicitous beginnings, the idea of gimmickry soon spread. In Vladimir Nabokov’s novel “Invitation to a Beheading,” from 1935, a mother distracts her imprisoned son from counting the hours to his execution by describing the “marvelous gimmicks” of her childhood. The most shocking, she explains, was a trick mirror. When “shapeless, mottled, pockmarked, knobby things” were placed in front of the mirror, it would reflect perfectly sensible forms: flowers, fields, ships, people. When confronted with a human face or hand, the mirror would reflect a jumble of broken images. As the son listens to his mother describe her gimmick, he sees her eyes spark with terror and pity, “as if something real, unquestionable (in this world, where everything was subject to question), had passed through, as if a corner of this horrible life had curled up, and there was a glimpse of the lining.” Behind the mirror lurks something monstrous—an idea of art as device, an object whose representational powers can distort and devalue just as easily as they can estrange and enchant.

Editorials

Stakeholder vs. Shareholder Capitalism: What Is Ideal Today?

Haywood Kelly:

At Morningstar, we’re proud that our research teams not only operate

independently but that our analysts are encouraged to explore ideas and

raise contrarian viewpoints. The enemy of any research organization is

groupthink. A research organization needs to hire people who aren’t

afraid of challenging the status quo and who are always thinking about

how to foster a culture where people feel comfortable speaking up and

encouraging us all to think harder and sharper.

And we debate just about everything. Is the market overvalued? Should

private equity be allowed into retirement plans? What categories are

most suited to active investors? How much should an annuity cost? And

I’d say one of the hottest areas of debate these days is ESG. Does ESG

help or hurt investing performance? What ESG risks are truly material to

cash flows? What should be included in a “globe rating,” and on and on.

Within the field of sustainable investing and with it evolving so rapidly, there is really no facet that we don’t debate. And today, we’ve asked a group of researchers from across Morningstar to represent opposing sides of a particular ESG argument. But we didn’t have to look far for one that’s taken centerstage in 2020.

Editorials

HILL: The Great Reset

If you haven’t heard about The Great Reset yet, you will.

Soon.

Joe Biden’s “Build Back Better” slogan, of which no one knew the meaning or purpose, is a direct lift from The Great Reset Manifesto, let’s call it, concocted by the dreamy-eyed elites of the world who attend annual ritzy, star-studded winter retreats in Davos, Switzerland under the auspices of the World Economic Forum.

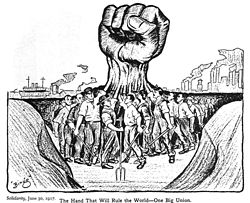

“In short” the wealthy elites of the world proclaim to the rest of the world, “we need a ‘Great Reset’ of capitalism.”

To save the world, these elites demand “the world must act … to revamp all aspects of our societies and economies, from education to social contracts and working conditions; …every country… must participate, and every industry, from oil and gas to tech, must be transformed”.

In other words, these elites demand that the entire world embrace socialism; impose much higher wealth taxes, which they will avoid paying, that’s a given; promulgate onerous regulations on banking and industry; and pass massive Green New Deals, which would “only” cost U.S. taxpayers and consumers $93 trillion to implement.

Liberal socialists never say anything about cutting government spending, lowering government regulatory burdens on business and people, getting rid of archaic government programs that have been proven ineffective, or removing legal barriers for people who want to start a business and provide a better life for their family.

Liberal socialists simply believe a lot more government is good. Conservatives don’t. It is pretty much that simple.

Every command issued by Great Reset/One World Government proponents strikes at the core of American individualism. American individualism and self-initiative led to the creation of such ground-breaking innovations as the IPhone, Amazon and Google, nothing close to which has ever been invented under socialist or communist regimes. Wait until the Great Reset dries up American innovation; Millennials and liberals will then see the adverse side of too much governmental control of our economy, then they will be ready for more free market capitalism.

Americans should understandably feel a little queasy when they hear Prince Charles or Canadian PM Justin Trudeau gush about how the COVID pandemic provides the “perfect opportunity” to change everything. Only totalitarians at heart think a pandemic or crisis is “a great time to impose their will on the world.” Hitler took power during the post-WWI economic depression in Germany to “restore the Fatherland,” to name perhaps the worst case in recent history.